Rabies

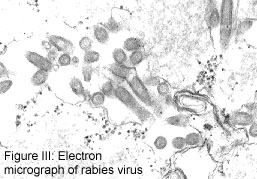

is caused by members of the RNA virus genus Lyssavirus, family Rhabdoviridae.

Rabies infection characteristically produces a rapidly progressive

encephalomyelitis (inflammation of the brain and spinal cord), and

should be considered as a possible cause of any such illness in

humans or other animals.

Rabies

is caused by members of the RNA virus genus Lyssavirus, family Rhabdoviridae.

Rabies infection characteristically produces a rapidly progressive

encephalomyelitis (inflammation of the brain and spinal cord), and

should be considered as a possible cause of any such illness in

humans or other animals.

Early symptoms of rabies are non-specific, but often include pain or paresthesia at the inoculation site. The disease progresses to an acute neurologic phase characterized by delirium, convulsions, muscle weakness, and paralysis. Spasms of the swallowing muscles can lead to a fear of water (hydrophobia), and may be precipitated by blowing on the patient's face (aerophobia). Not all persons exposed to rabies virus develop disease, but if symptoms do occur, rabies is almost invariably fatal -- usually within 10 days. There are case reports of three people who survived the disease in the 1970s10,5,11,12. All three had received some pre- or post-exposure treatment with the duck embryo vaccine or suckling mouse brain vaccine (vaccines that are no longer used in this country). A fourth documented case was reported in 1992 in a boy who received partial postexposure treatment.15

| Diagnosing Rabies in Humans: Because rabies is often not considered during the evaluation of patients with acute encephalitides, human rabies cases are usually identified after death. Antemortem diagnosis is possible, however, by analyzing the saliva, cerebrospinal fluid, skin (from the posterior neck), and serum of a symptomatic patient. Brain biopsy material can also be examined for rabies. Providers wishing to submit specimens for testing should contact the Communicable Disease Epidemiology Section at (206) 361-2914 to expedite such an evaluation. |

All cases of suspected rabies in animals should be reported

immediately to the local

health department and to the State Veterinarian's office at (360)

902-1878. Veterinarians may find additional diagnostic information

at the online Consultant

maintained by the Cornell University College of Veterinary

Medicine, or by contacting the local health department for a

referral to an expert on veterinary aspects of rabies.